Real Estate Dealer or Real Estate Investor Taxation — Don’t Get Caught In a Taxation Trap

Real estate investing can be lucrative with proper planning and execution, albeit if you’re not careful or have an experienced tax advisor, you could learn after the fact you owe much more in tax than you expected or planed for.

Here, we’ll discuss the differences in tax treatment

Most people go into real estate with the belief their profits will be taxed at the much more advantageous and lower capital gain rate. However, depending on the nature of your real estate investing, you may find out that not all real estate is treated as investments (even if it ‘feels’ that way).

While some go into real estate with the intention of simply fixing up properties and flipping them for quick gains, often it’s a better strategy, at least for some of the purchases and sales, to structure your objectives with the intention of renting the real estate, at least for a while prior to selling.

The reason is relatively simple to understand. As a real estate dealer, you will be taxed the same as any other business operator, including self-employment tax and the often higher ordinary tax rate.

Let’s first compare the differences in taxation:

- Single filers: Taxable income up to $48,350.

- Married filing jointly: Taxable income up to $96,700.

- Married filing separately: Taxable income up to $48,350.

- Head of household: Taxable income up to $64,750.

- Single filers: Taxable income between $48,351 and $533,400.

- Married filing jointly: Taxable income between $96,701 and $600,050.

- Married filing separately: Taxable income between $48,351 and $300,000.

- Head of household: Taxable income between $64,751 and $566,700.

- Single filers: Taxable income over $533,400.

- Married filing jointly: Taxable income over $600,050.

- Married filing separately: Taxable income over $300,000.

- Head of household: Taxable income over $566,700.

Let’s compare to the current Ordinary Federal Income Tax Brackets (of course, if you live in a state with income tax, how the state treats capital gains versus ordinary, if any difference, influences your after-tax income also).

2025 Ordinary Federal Income Tax Brackets (Married Filing Jointly)

For tax year 2025, taxable income for MFJ is subject to these marginal rates:

10% $0 – $23,850

12% $23,851 – $96,950

22% $96,951 – $206,700

24% $206,701 – $394,600

32% $394,601 – $501,050

35% $501,051 – $751,600

37% over $751,600

However, for those with earned income, the tax burden is not over yet. A taxpayer will generally have to factor self-employment tax as well.

Self-employed individuals pay a combined Social Security and Medicare tax of 15.3% on net earnings from self-employment (12.4% OASDI up to the Social Security wage base; 2.9% Medicare with no cap). For 2025, the Social Security wage base is $176,100 (generally, this is the maximum earned income in 2025 subject to self-employment tax).

Examples often make the point clear, so let’s examine the difference in after-tax income for a real estate dealer compared to a real estate investor with income of $300,000 with a given property(ies) held for more than one year. This is why as a real estate investor you want to understand your tax exposure with different intensions for the same property(ies).

The anticipated federal income tax for a business owner is about $64,500*, while the anticipated federal income tax for a Real Estate Investor with the same $300,000 profit is about $27,900*. (ok, for full tax treatment transparency, it should be noted that some deductible expenses may be available to a Real Estate Dealer that is not available to a given Real Estate Investor, which may have the effect of decreasing the difference)

In other words, the Real Estate Dealer keeps about $235,434 after-tax income, while the Real Estate Investor keeps about $272,100* in their pocket, or a $36,671 difference in federal income tax paid, for the same amount of income.

Let’s look at how we arrived at the numbers starting with the Real Estate Investor:

Long-Term Capital Gains Federal Tax

Profit = $300,000 – $30,000 standard deduction = $270,000

0% on the first $96,700

15% on the remaining $173,300 → 0.15 × $173,300 = $25,995

Calculate Net Investment Income Tax (Obama Care Tax)

MAGI threshold for MFJ = $250,000

MAGI (here full gain) – threshold = $300,000 – $250,000 = $50,000

NIIT = 3.8% × lesser of (net investment income $300,000, or MAGI excess $50,000) = 0.038 × $50,000 = $1,900

Total tax

Long-Term Capital Gains Federal Tax: $25,995

NIIT: $1,900

Total: $27,895

After-tax proceeds

$300,000 – $27,895 = $272,105

Next, we’ll look at how we arrived at the numbers starting with the Real Estate Dealer*:

| Gross Schedule C profit | $300,000 | |

| Net SE earnings | 92.35% × $300,000 | $277,050 |

| Self-Employment tax | 12.4% on first $176,100 + 2.9% on all $277,050 | $29,858 |

| Deductible half SE tax | ½ × $29,858 | $14,929 |

| Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) | $300,000 – $14,929 | $285,071 |

| Taxable income before QBI | $285,071 – $30,000 | $255,071 |

| 20% of QBI | 20% × $300,000 | $60,000 |

| 20% of TI before QBI | 20% × $255,071 | $51,014 |

| QBI deduction | Lesser of the two → $51,014 | |

| Taxable income after QBI | $255,071 – $51,014 | $204,057 |

| Ordinary income tax | MFJ rates on $204,057 (10/12/22/24% brackets) | $34,708 |

| Total tax burden | $29,858 (SE tax) + $34,708 (income tax) | $64,566 |

| After-tax income | $300,000 – $64,566 | $235,434 |

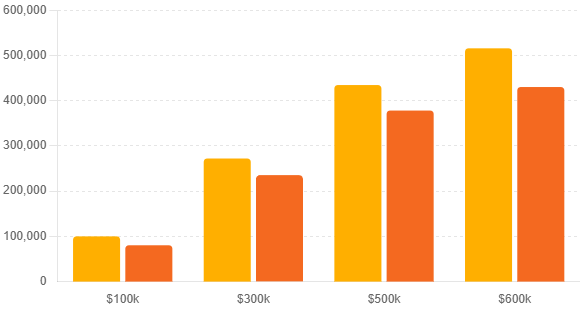

As the table and numbers demonstrate, all else being equal, it’s far better to obtain $300,000 in income as a result of real estate investing, and here’s the impact for various income differences.

If you’re involved in real estate rentals and flipping, If I didn’t have your attention before, I likely have it now. Let’s take a look at what the IRS looks at in order to determine how to classify both any single transaction, as well as the taxpayer generally.

Are you an “investor” or a “real estate dealer” in the eyes of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS)?

This classification is not merely a semantic detail; As illustrated earlier, it fundamentally alters how your profits and losses are treated and taxed (or deducted), whether self-employment taxes apply, and your eligibility for certain tax benefits and expenses. This is particularly pertinent for those engaged in the popular practice of “flipping” houses, where the lines can easily blur.

Let’s examine the authoritative IRS rules, relevant Internal Revenue Code (IRC) sections, pivotal caselaw, and the multi-factor tests courts use to make this determination. Our goal is to equip you with the knowledge to have a basic understanding these complex rules, identify potential pitfalls, and strategically position your activities to align with your intended tax outcomes.

The IRS Definition: What Constitutes a Real Estate Dealer?

The Statutory Backbone: IRC Section 1221 and the Definition of a Capital Asset

- Gains from the sale of such non-capital (dealer) property are treated as ordinary income, taxed at the taxpayer’s regular income tax rates.

- Losses from the sale of such property are treated as ordinary losses, which are generally fully deductible against other ordinary income without the limitations that apply to capital losses.

- Gains from the sale of capital assets held for more than one year are typically long-term capital gains, which often benefit from lower, preferential tax rates compared to ordinary income rates.

- Losses from the sale of capital assets are capital losses. These can be used to offset capital gains. However, if capital losses exceed capital gains, the amount of net capital loss that an individual taxpayer can deduct against ordinary income is limited (currently $3,000 per year, with any excess carried forward to future years).

Why the Distinction is a Game-Changer: Key Tax Ramifications

- Tax Rates on Profits: As highlighted, dealers pay ordinary income tax rates on their profits, which can be significantly higher than the long-term capital gains rates available to investors.

- Self-Employment Taxes: This is one of several major considerations. Net profits from real estate dealer activities are generally considered earnings from self-employment and are therefore subject to self-employment taxes, which cover Social Security and Medicare contributions (currently a combined rate of 15.3% on the first tier of earnings, with Medicare continuing at 2.9% or 3.8% thereafter). Gains from the sale of investment property by an investor are not subject to these taxes. For active flippers, this can amount to a substantial additional tax burden.

- Deductibility of Expenses:

- Dealers typically report their income and expenses on Schedule C (Form 1040), Profit or Loss From Business. They can generally deduct all ordinary and necessary business expenses associated with their real estate dealing activities, such as marketing, commissions, repairs (as current expenses if not capital improvements), utilities for properties held for sale, and home office expenses if applicable.

- Investors report gains and losses from sales on Schedule D. Rental income and expenses are reported on Schedule E. Investment-related expenses (like investment interest, property taxes, and management fees for investment properties not primarily held for sale) are subject to various rules and limitations. For instance, investment interest expense is generally deductible only to the extent of net investment income. So, it must be highlighted, that for some, a property that is inventory instead of an investment MAY result in a lower tax obligation, especially if the sale results in a loss.

- Section 1031 Like-Kind Exchanges: A powerful and often used tax-deferral strategy for real estate investors is the Section 1031 like-kind exchange, which allows an investor to defer capital gains tax if they sell an investment property and reinvest the proceeds in another similar investment property. However, property held “primarily for sale” – i.e., dealer property or inventory – is explicitly not eligible for Section 1031 treatment.

This means flippers classified as dealers cannot use this deferral mechanism for their flipped properties. For those subscribing to Buy, Borrow, and Die strategy of Real Estate Investing, with the goal of passing down wealth to the next generation, this tax treatment could have devastating impact for those without proper guidance.

- Passive Activity Loss Rules: While generally more relevant to rental activities, the characterization as dealer or investor can interact with passive activity loss (PAL) rules under IRC Section 469, especially if the taxpayer has other passive activities.

When the Lines Blur: The Courts’ Multi-Factor Analysis

- The Nature and Purpose of the Acquisition of the Property: What was the taxpayer’s original intent when they acquired the property? Was it for long-term appreciation, to generate rental income, for personal use, or was it acquired with the immediate or primary goal of reselling it at a profit? Documentation from the time of acquisition, such as business plans or corporate minutes, can be relevant.

- The Purpose for Which the Property Was Held During the Ownership Period: Did the taxpayer’s intent change while they owned the property? For example, a property initially acquired for investment might later be developed and marketed for sale, potentially changing its character. The consistency of the taxpayer’s actions throughout the holding period is scrutinized. In other words, just because a taxpayer started with one purpose, doesn’t mean it can’t change to another.

- The Frequency, Number, and Continuity of Sales: This is often a very significant factor. A pattern of frequent, numerous, and continuous sales of properties over a period is strongly indicative of a business operation (dealer status). Isolated or infrequent sales are more consistent with investment activity.

A house flipper who completes several transactions per year is more likely to be viewed as a dealer than someone who sells an investment property every few years. There is case-law regarding one single buy/sell of property that determined the taxpayer was in the business of real estate, instead of investing, so it’s important to understand there is NO RED LINE to be guided by.

- The Extent of Development and Improvements Made to the Property: Substantial improvements, subdivision of land, construction, or extensive renovations aimed at making the property more marketable and increasing its sale price can point towards dealer status. Improvements that are primarily for maintaining a rental property or preparing it for long-term holding are less likely to indicate dealer activity.

- The Extent and Substantiality of the Transactions: This involves looking at the dollar volume of sales, the amount of income derived from these sales, and the proportion of the taxpayer’s total income that comes from these real estate activities. If real estate sales represent a significant and regular source of income, it leans towards dealer status.

- The Nature and Extent of the Taxpayer’s Business and Other Activities: Is the taxpayer primarily engaged in another full-time profession or business, with real estate activities being a sideline? Or do real estate sales activities constitute their primary business and occupy the majority of their time and effort? Does the taxpayer hold themselves out to the public as a dealer in real estate (e.g., through a business name, office, or professional licenses used for dealing)?

- The Extent of Advertising, Promotion, or Other Sales Efforts: Active and extensive marketing efforts, such as listing properties with multiple brokers, running advertisements, holding open houses, actively soliciting buyers, or maintaining a sales office, are characteristic of a dealer. Passive holding with minimal or no sales effort until a decision to liquidate an investment is made aligns more with investor status.

- Listing the Property for Sale Directly or Through a Broker: While both investors and dealers may use brokers, the manner, timing, and extent of such listings can be part of the overall picture. For example, immediately listing a property for sale after acquisition and renovation is a dealer-like activity.

- The Taxpayer’s Own Statements and Tax Reporting History: As vividly illustrated in the Musselwhite case, how taxpayers describe their activities in legal documents, correspondence, and, crucially, on their tax returns (e.g., reporting on Schedule C versus Schedule D, classifying assets as inventory or investments on balance sheets) can be highly influential. Consistency is key, and attempts to change classifications without a clear change in underlying facts can be viewed skeptically by the IRS and courts.

Navigating the Pitfalls: Common Traps for Real Estate Investors (Especially those that both Flip and invest in Properties)

- High Volume and Frequency of Transactions: The business model of flipping often relies on completing multiple buy-renovate-sell cycles within a year or a relatively short period.

- Short Holding Periods: Properties are typically not held for long-term appreciation in a flipping scenario; the goal is a quick turnaround.

- Substantial Improvements Primarily for Resale: Renovations in flips are almost always geared towards maximizing the immediate resale value and appeal to potential buyers, rather than for long-term rental or personal use. This is really fact driven though. For example, adding a bedroom may be for higher rental income, or sale price.

- Active and Continuous Marketing and Sales Efforts: Successful flipping usually requires aggressive marketing to find buyers quickly once renovations are complete. Investors typically are aggressive in attempting to find a renter.

- Real Estate Activities as a Primary Focus: For many successful flippers, these activities can become their primary source of income and occupy a significant portion of their time and resources, resembling a full-time business.

- Clear Intent to Resell at Acquisition: In most flipping scenarios, the property is acquired with the clear and primary intention of reselling it for a profit in the near future. If you’re listing the property within a few weeks of purchase, that is a very different fact that not listing a property for even a few years.

- Inconsistent or Opportunistic Tax Reporting: As the Musselwhite case demonstrated, attempting to characterize properties as investments on some tax returns or for some purposes, and then as dealer property when it suits (e.g., to claim ordinary losses), can be problematic if not supported by a genuine change in facts and circumstances. This goes back to sustenance over form as discussed previously.

- Lack of Segregation: If an investor also engages in some dealing activities, failing to clearly segregate these activities (e.g., through separate legal entities and meticulous record-keeping) can lead to all properties being tainted with dealer status. Creating and using separate entities can allow the taxpayer to have the “flips” in one entity, while the investments remain directly or indirectly (through a disregarded LLC for example) owned.

Charting a Course for Investor Status: Strategies and Best Practices

Clearly Document Investment Intent from the Outset: At the time of acquiring a property, thoroughly document your intention. Is it for long-term capital appreciation? To generate rental income? For future personal use? This documentation can be in the form of corporate minutes (if acquiring through an entity), personal investment plans, correspondence with advisors, or loan application details that specify investment purpose.

- The IRS and courts place significant emphasis on the taxpayer’s intent at the time of acquiring a property. This intent should ideally be to hold the property for long-term appreciation, to generate rental income, or for other investment purposes (e.g., future development for long-term holding, or even personal use that later converts to investment). Simply stating this intent is not enough; it must be supported by contemporaneous documentation.

Practical Examples & What to Document:

- For Individuals: Create a personal investment memorandum for each property acquired. This document should outline your investment goals for that specific property (e.g., “Acquire and hold for 5–7 years for rental income and long-term capital appreciation,” or “Purchase as a potential future primary residence after a period of rental”). Include financial projections that support a long-term hold strategy (e.g., projected rental income, anticipated appreciation based on market trends, not quick flip profits).

- For Entities (LLCs, Corporations): Formalize investment intent in corporate resolutions or LLC operating agreement minutes at the time of acquisition. These documents should explicitly state the investment purpose for the specific property. For instance: “Resolved, that XYZ LLC shall acquire the property at 123 Main Street for the primary purpose of long-term rental income generation and capital appreciation over an anticipated holding period of no less than five years. Or 123 Main Street is purchased as a repair and sell property to be sold as quickly and at the highest value reasonable.”

- Loan Documentation: Ensure that loan applications and financing documents consistently state the purpose as “investment” rather than “business” or “resale.” Lenders often require this distinction, and it can serve as supporting evidence. If approach your lender for the purchase of a property and tell them you anticipate repairing and selling it within a few months, it’s a challenge to later argue with the IRS the property is an investment, and in fact, could result in evidence of tax evasion and/or fraud.

- Correspondence: Retain emails or letters with real estate agents, partners, or financial advisors that discuss the long-term investment strategy for the property before or at the time of purchase.

- Avoid Contradictory Language: Scrutinize all early documentation to ensure there’s no language suggesting an intent for quick resale (e.g., phrases like “quick flip potential,” “immediate resale value,” or marketing plans for sale drafted before or at acquisition, unless that is your desired intent. It should and needs to be said with as much enthusiasm that you do NOT want to create a paper trail designed to evade taxes or to commit tax fraud).

Prioritize Longer Holding Periods:

While there is no definitive bright line in the sand a taxpayer can rely upon, longer periods of rental activity compared to a quick sale is often guiding.

While the Internal Revenue Code specifies a holding period of “more than one year” to qualify for long-term capital gains, this is merely the minimum threshold for the preferential tax rate.

For the broader Real Estate Dealer vs. Real Estate Investor determination, significantly longer holding periods provide much stronger evidence of investment intent. Frequent purchases and sales, even if each property is held for (slightly) over a year, can collectively resemble dealer activity.

The takeaway is a longer holding period does, all else being equal, tend to lean towards Real Estate Investing, while shorter periods do not. Holding a property for even three or four years doesn’t in itself make it an investment instead of inventory.

- Practical Examples & Considerations:

- Aim Beyond the Minimum: Strive for minimum holding periods measured in multiple years (e.g., 3–5 years or more) for properties you intend to classify as investments. This demonstrates a commitment to long-term growth rather than quick profits from market timing or rapid turnover.

- Document Reasons for Shorter Holds (If Unavoidable): If an investment property must be sold sooner than initially planned due to unforeseen circumstances (e.g., a sudden job relocation, unexpected major repair costs making the investment untenable, a significant unsolicited offer that dramatically accelerates long-term appreciation goals), thoroughly document these reasons. This can help counter the presumption that the property was initially acquired for a quick sale.

- Rental History: If the property was rented out for a substantial portion of the holding period, this strongly supports investment intent, even if the overall holding period is not exceptionally long. Maintain detailed rental agreements, income statements, and expense records.

- Practical Examples & Considerations:

- This factor is a cornerstone of the dealer analysis. A high volume of sales, occurring regularly and continuously, strongly suggests that the taxpayer is in the business of selling real estate. Isolated or sporadic sales are more characteristic of an investor liquidating assets.

- Practical Examples & Strategies:

- Pace Your Sales: If you own multiple investment properties, try to pace their sales over several years rather than selling many in a single tax year, unless there’s a compelling, documented investment reason (e.g., portfolio rebalancing towards a different asset class, significant market shift).

- Avoid a “Production Line” Appearance: If your activities resemble an assembly line—buy, renovate, sell, repeat, with multiple properties in different stages simultaneously—this is a red flag. Each investment property should ideally have its own distinct investment lifecycle.

- Compare to Other Income: If income from property sales becomes your primary or most substantial source of income, and sales are frequent, it becomes harder to argue against dealer status. Maintaining other significant sources of income can help.

The nature and extent of improvements made to a property are closely examined. Improvements primarily aimed at preparing a property for long-term rental or enhancing its value for long-term appreciation are consistent with investor status. Conversely, extensive development, subdivision, or renovations solely designed to maximize immediate resale profit (like a cosmetic flip) can indicate dealer activity.

Practical Examples & Distinctions:

- Investor-Type Improvements: Necessary repairs (roof, HVAC), upgrades to attract long-term tenants (durable flooring, updated kitchens/baths suitable for rental wear and tear), improvements for safety or code compliance.

- Dealer-Type Improvements: Extensive cosmetic renovations focused on current buyer trends with the primary goal of a quick, high-profit sale; subdividing land into multiple lots for immediate sale; constructing new homes on spec for sale.

- Documentation: Keep detailed records of all improvements, including invoices and the rationale behind them. If renovations are substantial, document how they align with a long-term hold strategy (e.g., “Upgrading kitchen to attract higher-quality long-term tenants and reduce future maintenance costs”).

- Avoid “Staging” for Sale Too Early: While staging is common, if a property is extensively staged and marketed for sale immediately after acquisition and minor work, it can look like dealer activity.

Taxpayers who engage in both investment and dealing activities face a significant challenge. One common strategy is to conduct these activities through separate legal entities. For example, an LLC might be used for flipping properties (dealer activity), while another LLC or the individual directly holds properties for long-term rental (investment activity).

This requires absolute rigor in maintaining the separateness of the entities. Often, a S or C corporation tax treatment for the LLC is preferred for the properties the taxpayer is flipping.

For real estate beginners, if you hear some social media or otherwise ‘guru’ stating “real estate should never be held in an S Corp” you know you’re dealing with someone who doesn’t understand fully what they’re claiming to give advice on.

Practical Examples & Critical Safeguards:

- Separate Entities: Form distinct LLCs or corporations for Real Estate Dealing versus Investment. Each entity must have its own bank accounts, accounting records, and operational procedures.

- No Commingling: Absolutely no commingling of funds or assets between the dealer entity and the investor entity/individual. Properties must be acquired and held in the name of the correct entity from the outset.

- Different Business Plans: Each entity should have a clearly documented business plan reflecting its specific purpose (e.g., the dealer LLC’s plan focuses on acquisition, renovation, and quick resale; the investor LLC’s plan focuses on tenant acquisition, property management, and long-term appreciation).

- Arm’s-Length Transactions: If there are any transactions between the entities (e.g., the investor entity sells a long-held property to the dealer entity for development – a risky scenario), they must be conducted at arm’s length, as if between unrelated parties, and be thoroughly documented.

- Professional Advice is Non-Negotiable: This is my sale’s pitch of sorts, albeit it doesn’t make it any less true.…Any advanced strategy is fraught to the top with peril if not executed flawlessly. The IRS scrutinizes such arrangements closely for substance over form. You must consult with experienced tax advisors and legal counsel to structure and maintain this separation correctly. Failure to do so can result in the IRS disregarding the separate entities and tainting all activities.

- Detailed Explanation: If real estate activities are not the taxpayer’s sole or primary source of income and they maintain a distinct, full-time (or significant part-time) occupation or business in another field, this can lend weight to the argument that their real estate transactions are investments rather than a primary trade or business.

- Practical Considerations:

- Time Spent: The amount of time dedicated to real estate activities versus other occupational pursuits is relevant. If you spend 40 hours a week on your engineering job and 5–10 hours on managing your rental properties, it supports investor status for the rentals. If you spend 40 hours a week flipping houses and have no other job, as you likely can guess, it points to dealer status for the flips.

- Holding Out to the Public: Avoid holding yourself out as a full-time real estate dealer if you are trying to maintain investor status for certain properties and have another primary profession.

Consistency in how you report your real estate activities on your tax returns year after year is crucial. The IRS and courts look for patterns. Switching how a property or activity is reported without a clear, substantial, and well-documented change in the underlying facts and circumstances can trigger scrutiny and be viewed unfavorably.

Practical Examples:

Correct Schedules: Report rental income and expenses for investment properties on Schedule E. Report gains/losses from the sale of investment properties on Schedule D (and Form 8949). Dealer activities are typically reported on Schedule C.

Balance Sheet Classification (for entities): If your entity prepares balance sheets, ensure properties held for investment are classified as such (e.g., “Investment Property” or “Rental Property”) and not as “Inventory.”

Avoid Amended Returns to Change Character: Filing an amended return to change a property from investment to dealer (or vice-versa) simply to gain a tax advantage for that year is highly risky unless there’s been a genuine, documented change in how the property was held and its intended use.

Example of Justifiable Change: A property initially acquired and held as a rental for five years (reported on Schedule E) might genuinely be converted to dealer property if the investor decides to cease being a landlord, extensively renovates it specifically for sale, and then sells it. The facts and intent have changed. This change should be documented.

- The dealer versus investor distinction is one of the most litigated areas in tax law precisely because it is so fact-intensive. The rules are complex, and the stakes are high. Engaging with qualified tax professionals (CPAs or tax attorneys specializing in real estate) before you embark on significant real estate activities, and maintaining that relationship for ongoing advice, is the single most important step you can take.

- What Professionals Can Do:

- Strategic Planning: Help you structure your acquisitions and activities in a way that aligns with your desired tax status.

- Documentation Review: Advise on the types of documentation you need to maintain and review your existing records.

- Entity Structuring: Provide guidance on whether separate entities are advisable and how to set them up correctly.

- Transaction Analysis: Analyze specific proposed transactions to assess the risk of dealer classification.

- Audit Defense: Represent you if the IRS challenges your investor status.

- When to Consult: Before acquiring new properties, especially if your activity level is increasing; before selling properties, particularly if the holding period is short or significant improvements were made; when considering changes in how properties are used (e.g., converting a rental to a flip); or if you are concerned your activities might be approaching dealer status.

Conclusion: Proactive Planning is Your Best Defense

- Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT): High-income earners may also be subject to the NIIT, an additional 3.8% tax on investment income, including capital gains, if their modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) exceeds certain thresholds.

- Collectibles and Small Business Stock: Gains from collectibles (like art, antiques, and precious metals) and certain small business stock may be taxed at a maximum rate of 28%.

- Depreciation Recapture: When selling real estate where you’ve previously claimed depreciation deductions, a portion of the gain may be taxed at a maximum rate of 25%.

* A basic overview can only provide rough estimates due to changes and adjustments as a result of individual facts and circumstances, and does not include important considerations as to other deductions, direct deductible expenses, and other investment and/or business activity. In other words, without all the facts, it’s a BIG mistake to assume the tax treatment illustrated and exampled above will highly correlate to any taxpayer and especially to you. It’s vital for a taxpayer with active real estate exposure to discuss their particular situation and facts with a qualified real estate tax advisor.